- Sugar is a primary ingredient that is added to many processed foods

- Sugar is a cheap ingredient and makes foods more palatable

- Consuming sugar regularly and amounts greater than recommended is linked with many lifestyle related diseases including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease

- There are many simple and practical ways to reduce the intake of foods with added sugars like simple swaps and making your own treats

Introduction

The food we eat has changed drastically over the past 40 years. Our grandparents ate food that was sustainably-produced, fresh, nutritious and relatively unprocessed. Due to intensive farming practices and changes in the way food is manufactured, processed and marketed, there has been a considerable shift away from fresh, whole foods towards readily–available, convenience food that contain a myriad of preservatives, additives, flavour enhancers, sweeteners and, of course, sugar.

Sugar, easy to find and hard to avoid

Sugar, easy to find and hard to avoid

Sugar is everywhere in your diet, but you just might not know it. You can find added sugars in cereals, bread, juices, sauces, yoghurts, snack bars, “low-calorie foods” and most packaged foods. The reasons for this are straightforward: sugar is a cheap ingredient, makes food easier to store, and sell in large quantities compared to fresh, perishable foods and of course it makes food taste better.

- Added sugars are disguised in many forms, here is a short list of other names for sugars to look for on labels

- Fructose

- High fructose corn syrup

- Glucose

- Dextrose

- Invert sugar

- Maltodextrin

- Maize starch

- Corn starch

- Cane sugar

- Syrup

- Corn syrup

- Molasses

Important points to consider on sugar when reading food labels

- The closer ‘sugar’ or other names for sugar are to the top of an ingredient list the greater proportion of sugar in the product, and the greater proportion of calories from sugar

- 4 grams of sugar = 1 teaspoon

- The American Heart Association’s recommendations for sugar intake:

Men should consume no more than 9 teaspoons (36 grams or 150 calories) of added sugar per day.

Women should consume no more than 6 teaspoons (25 grams or 100 calories) per day.

Consider that one 330 ml can of fizzy drink contains 8 teaspoons (32 grams) of added sugar! For some people that’s more than the recommended intake for the full day consumed in a few minutes!

The health implications of eating foods with added sugar

Eating the odd sugar-sweetened food each week is not going to be detrimental to your health, particularly if you are regularly active; but eating these foods daily with limited physical activity certainly will. People unknowingly consume foods with added sugar on a daily basis, which reduces the overall quality of their diet and these added sugars are linked to increased risk of diseases such as obesity, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. The rate at which you digest your food has significant implications for your health. Our digestive system is highly evolved to break our food down slowly over time to produce energy for bodily functions and movement.

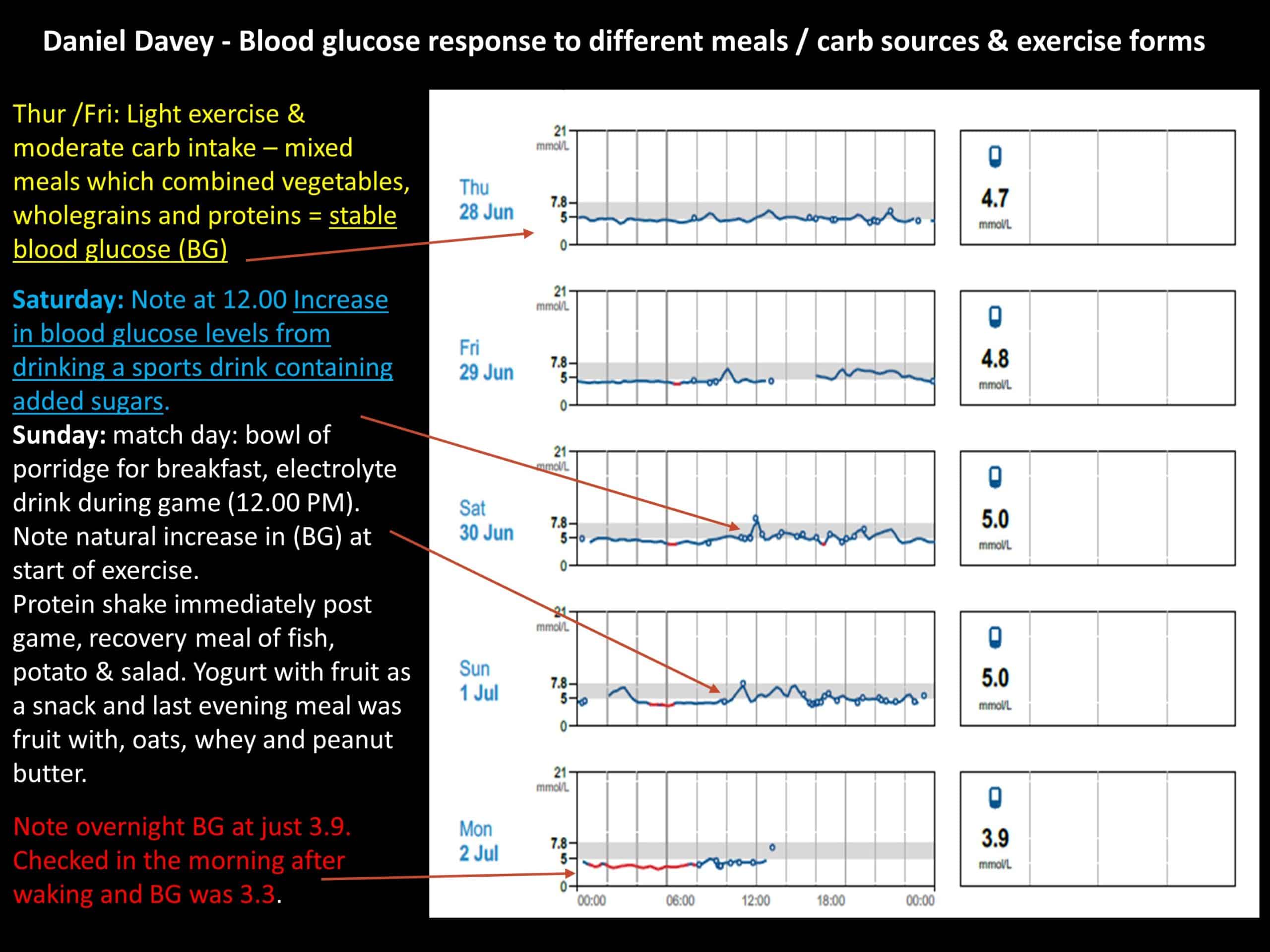

When we eat foods with added sugar, it results in a rapid rise in both blood glucose (blood sugar) and insulin (a hormone that regulates fat storage and blood sugar levels), which have implications for optimal energy metabolism and normal bodily functions. Here is a really interesting graphical insight on the impact of different food choices and exercise on blood sugar. This was conducted during a 2 week review of the impact of food choices, exercise and stress on blood sugar levels.

When we eat foods with added sugar, it results in a rapid rise in both blood glucose (blood sugar) and insulin (a hormone that regulates fat storage and blood sugar levels), which have implications for optimal energy metabolism and normal bodily functions. Here is a really interesting graphical insight on the impact of different food choices and exercise on blood sugar. This was conducted during a 2 week review of the impact of food choices, exercise and stress on blood sugar levels.

Eating sugar or foods with added sugars results in an increase in glucose in the blood stream. The rate at which blood glucose levels increase has significant implications for our health, particularly because of the hormonal impacts that occur from the excess glucose and insulin.

Eating sugar or foods with added sugars results in an increase in glucose in the blood stream. The rate at which blood glucose levels increase has significant implications for our health, particularly because of the hormonal impacts that occur from the excess glucose and insulin.

Another interesting recent development in how excess sugar impacts our health has been implicated in the link between our gut and our brain. In mice it has been shown that even in the absence of taste, mice still prefer foods or fluids with added sugar compared to foods without added sugar.

It was generally believed that it was the calories or the sweetness that was impacting the reward centre in the brain and this was driving consumption of more sweet foods, however new research implies it is more complex than that. It is now suggested that sensor molecules in the small intestine trigger a signal that travels via a nerve pathway from the intestines to the reward centre in the brain! It is also postulated that this is the reason why artificial sweeteners are not the simple solution for replacing foods and drinks with added sugars. It would make sense as you often hear the phrase about these foods and drinks being ‘just not the same’.

It was generally believed that it was the calories or the sweetness that was impacting the reward centre in the brain and this was driving consumption of more sweet foods, however new research implies it is more complex than that. It is now suggested that sensor molecules in the small intestine trigger a signal that travels via a nerve pathway from the intestines to the reward centre in the brain! It is also postulated that this is the reason why artificial sweeteners are not the simple solution for replacing foods and drinks with added sugars. It would make sense as you often hear the phrase about these foods and drinks being ‘just not the same’.

Below are some of the negative health consequences from consuming foods with added sugar:

- Poor appetite control leading to overeating

- Increases in triglyceride (fat) levels in blood

- Energy imbalances (blood sugar fluctuations)

- Increased LDL cholesterol (bad cholesterol)

- Alterations in gut health, increase in ‘bad’ gut bacteria

Tips on controlling the intake of added sugar

Fresh whole foods provide sustained energy and vitamins, minerals and antioxidants that keeps your immune system strong and your body in an optimal state of health when combined with regular physical activity. Avoiding foods with added sugar can be a challenging task as sugar is added to almost all packaged, processed foods.

Below is a list of key tips on how to make better food choices and reduce your intake of foods with added sugar:

To make constructive changes to your diet, you must take more responsibility for the food choices you make and, more importantly if you are a parent, for the children you feed.

To make constructive changes to your diet, you must take more responsibility for the food choices you make and, more importantly if you are a parent, for the children you feed.

Good nutrition relies heavily on:

- Preparation, creating a detailed shopping list and stocking fresh vegetables, fruits, nuts and seeds

- Having lunch boxes cleaned and ready to use

- Use dark chocolate as a replacement instead of milk chocolate

- Making healthy treats at home to replace the ones you will buy in a shop

- Swapping fizzy drinks for sparkling water and a dash of lime, drinking kombuca or sparkling green tea

- If you are having a treat, have it and enjoy it but don’t allow it to become a major source of energy in your diet

- Aim to reduce your intake of sweet, processed foods and sweet drinks such as sweetened juices and fizzy sweetened drinks

- Where possible, avoid buying food from convenience stores or petrol stations when you are hungry – unless, of course, they have a salad bar!

- If you are looking to sweeten a dish, add fresh fruit rather than sugar, syrups, jams or honey

- Always read food labels – if sugar is one of the first 5 ingredients listed, then it is best to leave that food on the shelf

These simple steps will go a long way to helping you consistently make better food choices and habits.

Real food tastes good

Real food tastes good

A diet that relies on foods with added sugar leads to a desensitised taste for naturally-sweet foods like fruits, unsweetened yoghurts, milk and nuts. The good news is that food tastes can be changed and cravings managed. Everyone knows that fruit and vegetables are important for health and vitality but many people don’t fully appreciate the implications of a diet that relies on processed foods with added sugar. Removing foods with added sugar will help you maintain an optimum bodycomposition and will hugely benefit your long term health. You might be asking yourself is sugar or eating foods with added sugar really that bad? Unfortunately the short answer is yes. Athletes are the exception in that regular high intensity exercise can off-set the implications of consuming sugar, but even then the need for sugar is predominantly during a very short window around exercise performance. If you are someone that needs to manage a sweet tooth it is important to use the practical suggestions above to begin reducing the amount and frequency of sugar in your diet.

References

Johnson RK, Appel LJ, Brands M, et al. Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;120:1011-20.

Lorena S. Pacheco, James V. Lacey, Maria Elena Martinez, Hector Lemus, Maria Rosario G. Araneta, Dorothy D. Sears, Gregory A. Talavera, Cheryl A. M. Anderson. Sugar‐Sweetened Beverage Intake and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in the California Teachers Study. Journal of the American Heart Association, 2020

Malik VS, Hu FB. Fructose and Cardiometabolic Health: What the Evidence From Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Tells Us. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Oct 6;66(14):1615-24

Tan, H.E., Sisti, A.C., Jin, H., Vignovich, M., Villavicencio, M., Tsang, K.S., Goffer, Y. and Zuker, C.S., 2020. The gut–brain axis mediates sugar preference. Nature, 580(7804), pp.511-516.